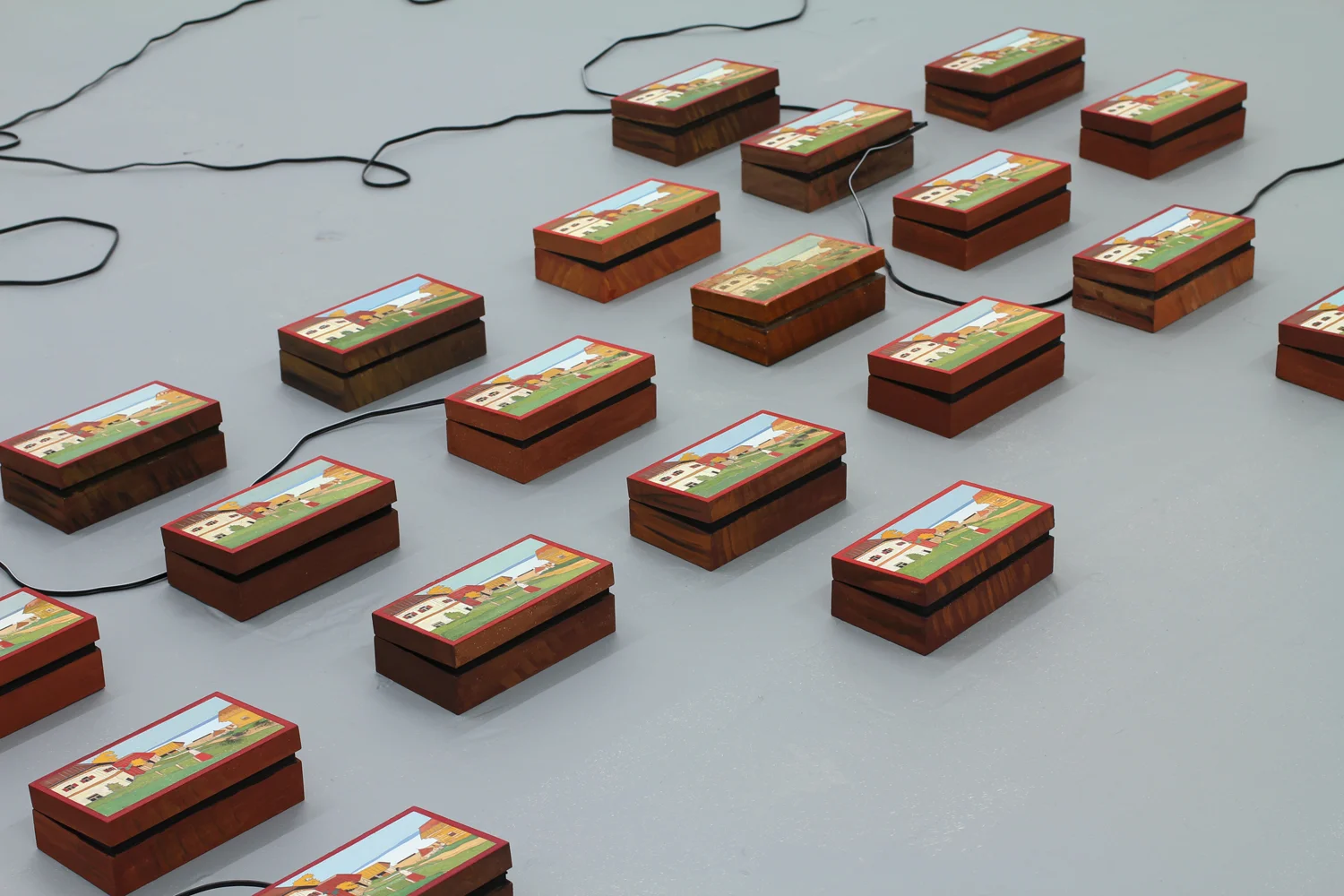

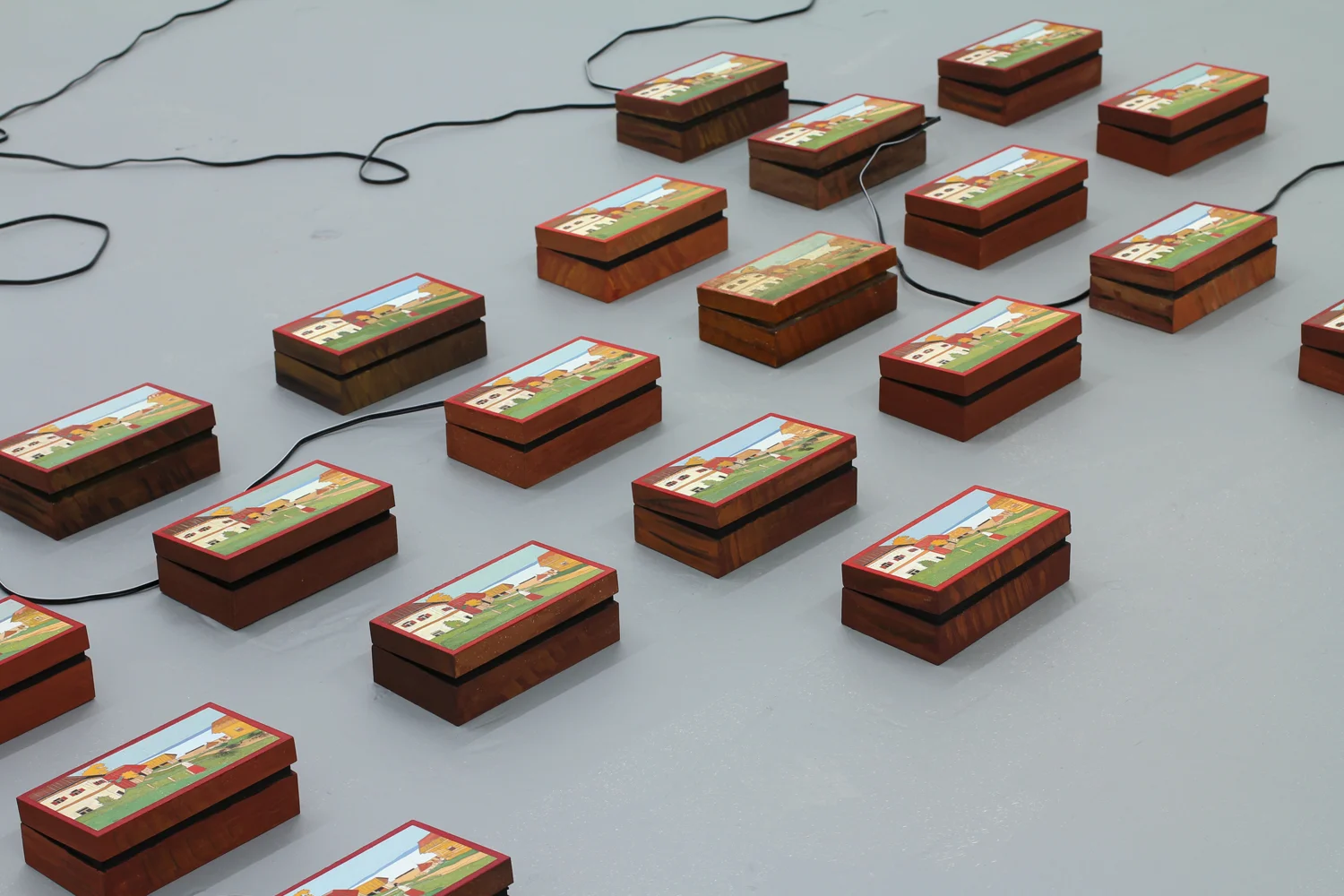

FIELD (WOODEN CYPHER)

6 - 23 May 2015

Opening Night | Thursday 7 May, 6-8pm

Chris Bond + Lynette Smith

Field (wooden cypher) is part of an open-ended investigation of the way we find meaning in things and events. To ‘find it’, it seems that all you have to do is be present. The world and its interpretive possibilities seem given to you in some way. Chris Bond and Lynette Smith are interested in how that happens and the blindness that, paradoxically, makes it possible to see that meaning as a given. We know there is no way of getting around that so we look instead for the possibility of pleasure (or another truth) in obscurity, uncertainty, incompleteness, deception and the inauthentic.

IMAGES | Lynette Smith, Field (Wooden Cypher), 2015, gouache on card, sound, dimensions variable| Images courtesy of the artist.

CONVERSATION

Field (Constant Light), Westspace + Field (Wooden Cypher), Blindside, 2015

Lynette

So, the hinge.

Chris

I’ve always been fascinated by hinged things. Flush hinges especially, they can fold into themselves, then further, the internal piece can be rotated to go behind the external piece, opening up another dimension, then twist back around again. I think it was Duchamp who made a door that when closed, opened up an entrance to another room. I like that potential in hinges.

Lynette

Normally a hinge stops at some point, otherwise it’s useless for the purposes for which we invented hinges. But if the only thing hinged is the hinge, then it will keep turning through itself (which makes it good for the purposes of art).

I think I performed a hinge action with your wooden box, twenty one times.

Chris

Now seems like a good time to ask, why twenty one?

Lynette

It is a way of saying that these paintings are just the same as those twenty-one drawings I showed at Sarah Scout last year (empty). No different in some important respect. You remember them.

Chris

Yes I do. We each have a logic that sits inside our methodology, and runs through what we do. With the Blindside works my thoughts ran to generating a few responses to the box in its current state, empty and ajar, and seeing how far (or how close) the collaboration, and the materiality of the box drags me from the way I usually do things.

Lynette

Did it drag you far? Or anywhere you didn’t expect?

Chris

Hmm, it did drag me a fair distance, which I’m pleased about…not sure where exactly, but somewhere at the periphery of where I like to operate. I’ve been looking over my shoulder at what you’ve been working on over the last few months, and paused at several points, changed the way I’ve completed things, or just stopped altogether. That’s not something I ordinarily do. It began with the challenge of the underpainting, the handover of which I found extremely difficult. I struggled with the incompleteness of it, having to stop halfway. Since then, maybe because of that early shock, I’ve relaxed a little and when I felt enough was enough, allowed myself to settle at a point, somewhere before where I’d usually end, and say, that’s it. How about you, how far have you been dragged, and where?

Lynette

Yes, I’ve been looking over my shoulder as well and darting to pick up things you’ve dropped. It has been one of the pleasures: to just be responsive and feel some lightness and the possibility of puns and other humour. I don’t know how much that will be apparent to anyone else but it is there. I was surprised how quick and clear and perfect some of my reactions were and how willing I was to act on them without more meditation over them. In general, I don’t like to react. And I don’t like to not know how it is going to turn out. But for this, I suffered both happily enough.

I think also that the collaboration made it easier to manage something that goes on with me, which is an explosion of possibilities in meaning and ways of looking at things. It’s out of control and I have always struggled with pulling one thing down to earth and let it be the thing.

With this I felt free to let things chain react because that’s what this collaboration is about.

So there has been a loosening of the grip.

Interesting that you struggled with the incompleteness. Incompleteness is one of my obsessions (along with ambiguity and opacity). This whole project is intrinsically incomplete. Perhaps that construction you made of the inner space of the box is a way of completing it, the box: you fill something that is designed to be filled. What do you think?

Chris

I think you’re right, it was an attempt by me to gain some kind of sense of completion. We’ve talked of our differences in this regard before, it may be the defining thing that separates our practices. I really struggle without a pre-determined end-point, to the extent where I’ll invent the end before I begin, usually through narrative, then work through and around to get to that end. So I found this experience difficult, but useful. Rewarded myself with the gift of the box inner, which gave me a lot of satisfaction, and some closure, excuse the bad pun. I think that maybe that’s another reason for the collaboration, to push us beyond the point of comfort.

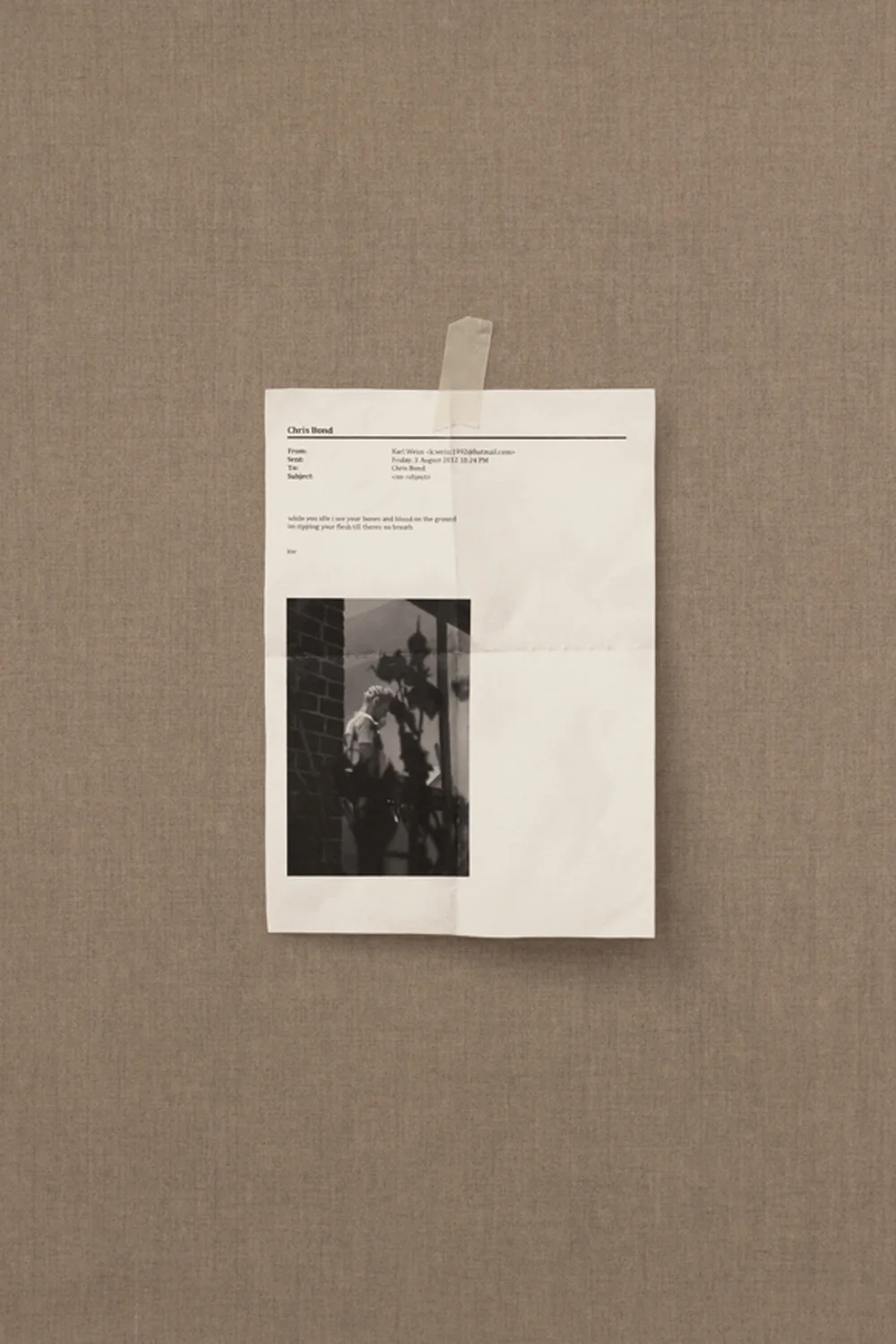

I’ve been meaning to ask how you felt in the weeks after I handed you the underpainting of the hands? I wanted to ask at the time but decided to leave you with it.

Lynette

Yes. You made the cypher palpable and visible.

It was easier than I thought it would be. I had your painting on the floor and I was mimicking the gesture in your underpainting and then trying other ways to shape my hands. So I saw closed and down contra your open and up and that seemed right. And in the process I turned your painting upside down from the sound of things. After that I thought I had a technical problem. I was going to paint the hands up to the wrists on your canvas and the rest, my arms, on a board which would extend the painting.

I think I found a way to paint egg tempera on your glue-sized canvas (because that was my intention-to use egg tempera) but I thought it would be ugly, both the surface of the paint and the placement of the figure on the ground.

So I moved my hands entirely onto the board and decided that my over-painting would be ‘over’ in a different sense. I started with the ink, which is my underpainting for the egg tempera, and decided to stop with that because there was the right parity between our two panels then.

That’s its history. I liked the opening and closing of the hands that do the opening and closing of the box. I like its incompleteness but completeness at the same time. And it led me to that second pair of paintings where I am holding an imaginary box in front of both myself and the viewer, which is an echo of the cypher, that word you chose, which means an empty symbol I think.

Chris

It’s interesting you say that, oddly coincidental. I’ve been physically imagining the empty content of the box since the moment of conceiving of it as the starter. When I say physically imaging, I mean that, actually physically rehearsing holding what once may have been its contents (going by the marks left behind by the objects that were once inside), an absence filled by air. There’s a neat bookend to the process too, as I’ve recently been reading about acting methodologist Michael Chekhov’s technique of the ‘psychological gesture’, a unique single repeatable physical gesture that acts like a psychological key to the way an actor might understand – and act upon – the characterisation they’re trying to embody. It’s an action that can be used during character development, rehearsal and during performance as a trigger. In retrospect it’s something I might have liked to test out further during the process of making.

Instead, I’ve tried to manifest the absence in objects. They occupy space, but I feel like they don’t ‘do’ a lot more than that. Maybe that’s why I like them so much.

Lynette

It seems that we have taken an object as our key and acted on it repeatedly, either to empty it out more or affirm that emptiness, or absence, as you say.

I think if we kept speaking we would find more co-incidences. It’s good that we talk as little as we do as we are working, otherwise we’d risk over-working those relations. The chain-reaction would stall.

I like things that don’t ‘do’ much. I’m in the grip of a strong antipathy for things that do stuff, including mean stuff; it’s an antipathy for things that are apt, fit and meet requirements; an antipathy for communication. I want the opposite.

I notice in you a desire to know about the history of a thing, in a particular way. You examined the cavity of the box for hints of what was in it, for example. You researched that book which was the start-object for the last exhibition. This is another difference between us and the way we work. You would say, perhaps: what do I make of this box, or this book. I would say, perhaps: what do I make of boxes and books.

Chris

Yes, I tend to look at the specific before the general. I like the idea that the key to the way things work might be found in minutiae, and so that’s the level I work at. I also feel I need to know something about the thing I’m looking at before starting. Especially so with the book at Westspace, I found it difficult to figure out what to do with it before I’d made some crude translations from the German, then it became clear what I needed to do. I find it hard working without a logic, and I expect the source to provide it. If I can’t find it in the object, I’ll fabricate a logic to work to.

Why do you think you have an antipathy for things that are apt, fit and meet requirements? Is it specific to making things?

Lynette

No, it’s quite general.

The source of the antipathy is my frustration with everything being interpreted, valued and judged exclusively according to whether and how it meets expectations and requirements which are often utilitarian in some way. It’s not that I think that this is not an appropriate attitude to things. Perhaps most things, most acts probably should be evaluated in that way–as long as you are always willing to look at and question those expectations and requirements. But if that’s your exclusive strategy for responding to things and actions then I think that’s a pretty impoverished attitude to experience and agency. I think why shut down the space of possibility with mean and tidy expectations about how things should be?

Why not be open to being challenged or surprised by an experience you don’t understand or didn’t imagine was possible or you can’t see its relevance or use or meaning? Why be so self-centred?

I think art can be one of those practices that looks more widely and thinks more deeply about what it’s like to be and act in the world. Instead it is always being dragged into doing work for others: entertaining, decorating, educating, making someone else’s ideas palatable to ‘people’. The funny thing that I’m finding is that trying to insist on that full space of possibility is interpreted as exclusive or negative.

What I am saying here connects with something you told me recently: people get angry or bothered when they discover that an apparent representation or narration is not ‘true’.

Chris

Yes, they react to being denied what they expect is a given – genuine representation. Which I’ve always found strange given what’s happened in art and theory since the 1960s in terms of the breakdown of ‘singular’ expression, and widespread mistrust of narrative forms. But they must still be compelling. I like the idea of making representations that on the surface appear to satiate those needs, and if that’s as far as people want to go in terms of interpretation, well… so be it, they may have missed the point but they’ve got something that gives them some comfort or delight and that’s fine…I’m not going to deny them that. However, within that narrow framework of fixed positions and utilitarian expectations there’s actually an enormous potential for expressions of liberty, for free play with false logics, fictions, and misrepresentations, and that’s where I get interested, and people tend to get frustrated. That frustration doesn’t occur in other fictional forms where fiction is expected, like literature or film where the fictional representation (the work) exists as a suggestive model that awaits an audience’s imaginative response or interpretation. In those forms, the audience and artist engage in a shared system of knowing, engagement, observation and disbelief that is collectively satisfying. I like the idea that something like that might be possible in a visual arts context but…and this may sound illogical, but I don’t think it’s possible through fiction, or deception.

I’ve only recently changed my position on this. It might only be possible through genuine representation. Specifically, forcing that kind of representation out through a process of self-deception. That’s what interests me at the moment. Whether it’s possible or not. Of course, it would be easier just to make something of one-self, execute some kind of simple genuine primary expression, but that’s never interested me.

Lynette

See, I would deny them that. I think it’s a childish desire and I won’t satisfy it. You must be a nicer person than me.

The only other practice which I have thought much about is the novel, which for most people is synonymous with fiction. I think the reverse is going on there. The expectation of fiction is so strong that people get angry or alienated by writers who think deeply about the form and do something different: like Musil, Sebald or Kundera, all writers that I love. Perhaps all practices of these kinds are burdened by expectations and norms that make life hard for the outliers.

Tell me more about the genuine representation. I feel like I have a parallel idea going on in my own practice but I don’t understand the ‘forcing that kind of representation through a process of self-deception’. Or maybe I have an inkling but tell me more about it.

And, yep, self-expression. Every one of my acts, all my behaviour, and yours and everyone else’s is expressive of ‘self’. What would be interesting for an artist is to challenge that idea of the self. This is something that you do and I think it has been built into this collaboration. We have a kind of leaky isolation going on where it’s not clear which of us might be the source of an idea or a metaphor or an image.

Chris

When I talk about forcing representation though self-deception I mean that I’m interested in finding ways of tricking the mind to incorporate the invented thoughts, feelings and actions of a characterisation, and acting them out as if they were real. So, getting primary expression out of an imagined body/mind. In acting it’s called incorporation, in performance and phenomenology it’s termed embodiment, and in psychology it’s known as self-deception. In the visual arts there’s no name for it because, as far as I can see, it’s yet to materialise as a methodology. Essentially it’s a kind of controlled dissociation. It’s a complex means to get somewhere outside the self, but I feel it has potential. You might be right in saying that our collaboration has got somewhere close to that point, perhaps without us being fully aware that it’s happening. It’s there in the process we’ve set up. Do you feel like something similar is happening in your own practice (outside the collaboration)?

Lynette

I see.

And, yes, definitely, I have parallel strategies which are about getting away from my own judgements and reflections on my own actions. For quite a few years, I was trying to work out how to design and perform an act that nulled out purpose, reflection and desires–but for it still to be an act, and only my own. The drawings have all been about this. Because I am interested in form (rather than narrative), my focus and my dilemma was the result of those acts: what counted as well-formed and what a form could reveal about its history (this is about ambiguity).

Just concentrating on the idea of ‘well-formed’–I think this is related to the idea of completeness. With most of those drawings there was no necessary place to stop. Should I stop when I thought it ‘looked good’? I am absolutely against that so I got into a terrible state trying to get away from it. Numbers and arbitrary relations were part of the strategy.

The last drawings (they feel like they are the last for the time being because my attention has shifted to another question), the empty targets, were all about this: removing all the dilemmas, as far as I could, about what counts as well-formed in some sense: colours, composition, closure in a ‘resolved’ form. What I have found though is that it is impossible to get away from your purposes, reflections and desires. What I have out of that is a heart-felt love and respect for dilemma, equivocation and ambiguity.

I think that is a strategy that is like what you are talking about.

- LYNETTE SMITH + CHRIS BOND