PRECIPICE

13 April- 7 May 2011

Jonathan McBurnie

Precipice presents a complex and stylised journey through the Australian landscape. Integrating the melodrama and kinetic energy of the superhero, Jonathan McBurnie draws together illness, biological war and the romanticism and tension inherent with the Australian landscape to comment upon real world environmental catastrophe and its collective psychological repercussions.

Artists today are relentless in their quest to articulate and explore ever-shifting modes of subjectivity. Central to this investigation is the body. Its pervasive regulation, in our time, has seen the body emerge as a key problematic in socio-cultural, political and economic mores. In art practice, as it is in any other field, the body struggles against the tyranny of mediatisation, surveillance, institutionalisation, and medicalisation to name but a few. It is in this last category however, that has had profound impact on artist Jonathan McBurnie’s practice. If the body, they say, is a battleground, then McBurnie has fought and won his fair share of battles. Surviving a year-long encounter with leukaemia and its aggressive treatment, McBurnie remains philosophical about his experiences, yet the threat of all-that-could-have-been remains in his recent body of work, Precipice.

Looking to Susan Sontag’s publication Illness as Metaphor, McBurnie found affinity in her discussion of the body as territory. In this he saw a clear nexus linking the body to site, or in his own context, to the Australian landscape. The desire to understand his practice within the great Australian tradition of landscape has inspired his current fascination with Australian history and literature, citing Robert Hughes The Fatal Shore as containing some of the most captivating and gruesome accounts of our colonialist history. In the same way that Hughes accumulates his account of colonisation through various sources, so too does McBurnie who provides an account of the colonisation of his own body by hostile cells. However, it may be unwise to seek recognisable Australian landmarks in McBurnie’s work. There are no antipodean cliches to be found in these landscapes; the artist preferring a post-atomic mise-en-scene that metaphorically portrays a traumatised body. And rather than Hughes’ narrative of history, McBurnie provides a narrative of his own life, collapsing past, present and future into allegorical assemblages that invoke psychological dimensions associated with suffering.

There is no denying that McBurnie’s unique narratives eschew schemata. His hand migrates as easily across the paper as he does from genre to genre. The confluence of space and plane is pushed to the limit within his work and it is with fluid precision that he demonstrates his mastery of bricolage. McBurnie’s characters – his ‘cells’ – are inspired by those in graphic novels, comics, art and historical reference and popular culture. Looking over his previous practice, one can establish a biological imperative at play in McBurnie’s tendency toward obsessive drawing. It is this very obsession that guided him through his own illness, and has remained a constant companion to the present day.

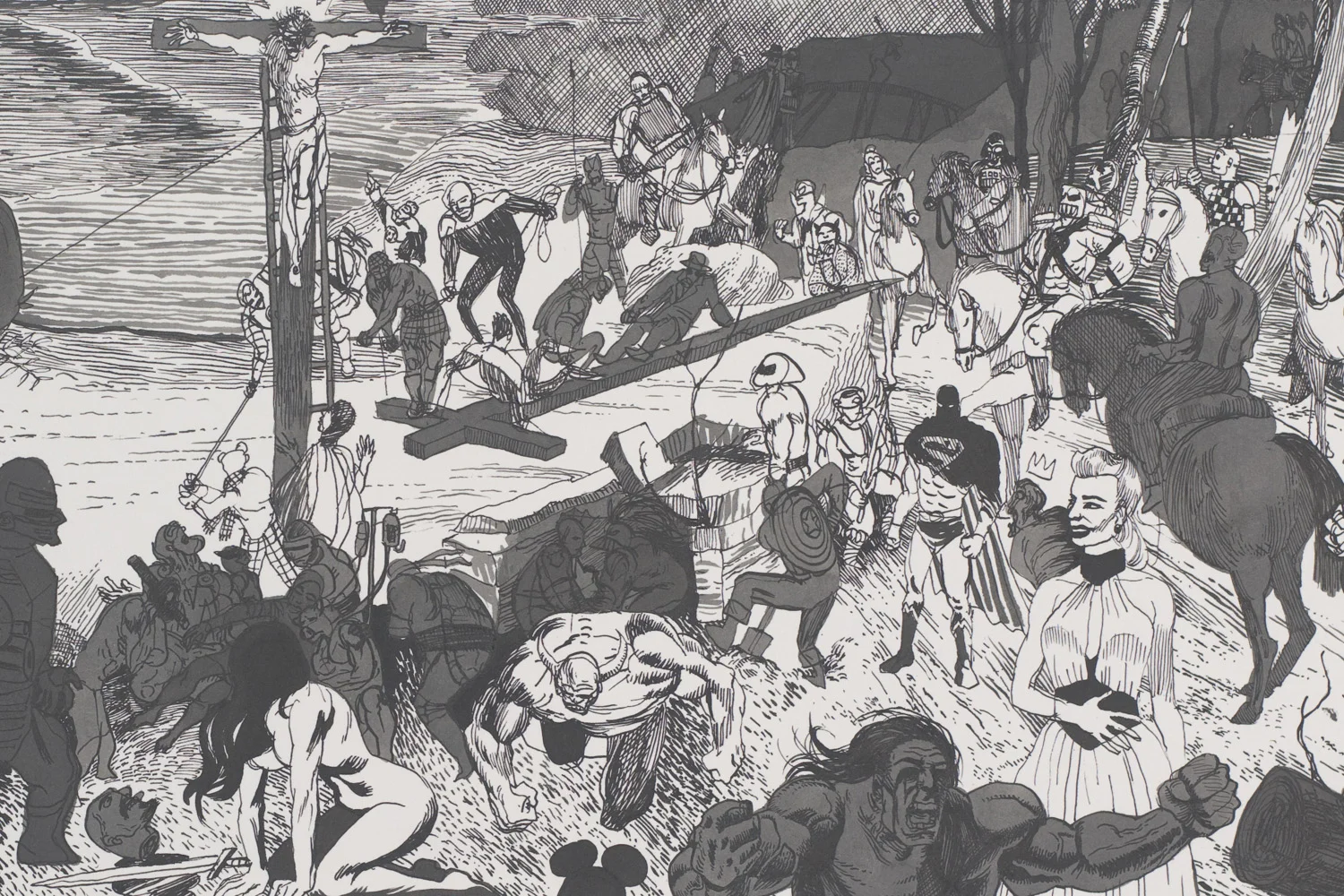

Whether as alter-ego, alibi or enemy, McBurnie inhabits multiple characters that blur his own identity, finding refuge in the surrogates who trawl his landscapes. He apprehends the state of chaos within and recasts himself sometimes as superhero, other times as anti-hero or villain in order to save the day. When the artist is asked to choose who he identifies with, he states that they are all, at once, ‘me and not me’. It is in this ambiguity that the artist finds great freedom, seeing it as a distancing mechanism achieved in order to cope with his experience of chemotherapy. This is evident when looking at Nothing is sacred to me, everything is sacred to me. In this work, the ‘body’ is out of control, multiple forces are in a battle of wills, and McBurnie takes on an agnostic position so to save himself from disappointment of defeat. One might recognise Tintoretto’s epic 1565 Crucifixion painting, but rather than aiming for iconoclasm, McBurnie recontextualises its figures with those he has long worshipped through comics, graphic novels and art history. Of course, the question remains, who or what is being sacrificed and for what purpose?

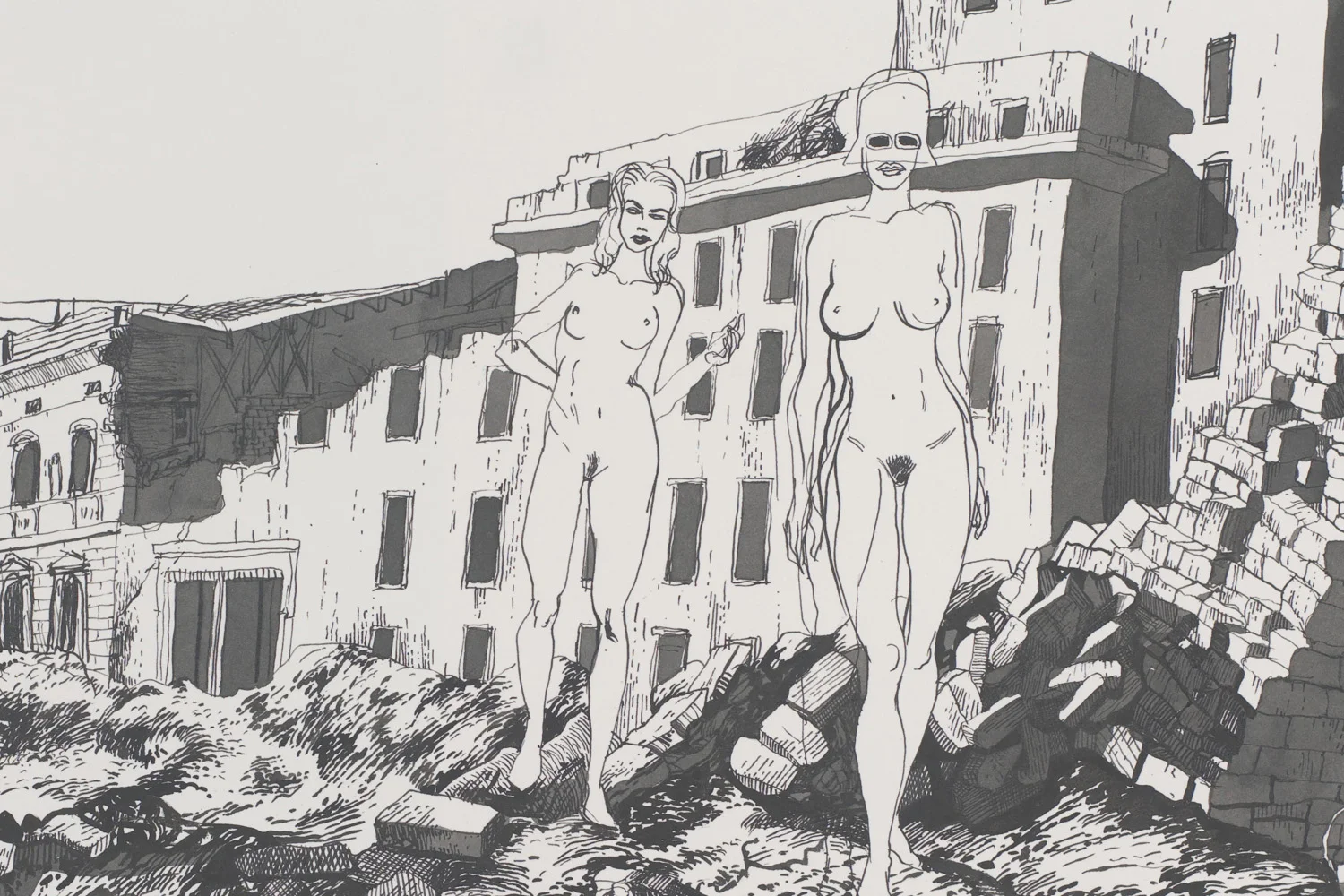

In works like We have to move on now and Leave the dead for the beasts to return to the earth, we see survivors make do, wandering like fugitives through the ruins of a conflict which now seems distant and unreal. They’ve struggled against metastasis, and the effects are seen metaphorically wearing the landscape of McBurnie’s sublimated body. Despite the source of inspiration for these works, they are not without humour. Anyone having the pleasure of conversation with the artist soon realises that this is not a tortured man; in fact, McBurnie has the all-clear from the medics. Indeed, this gallows humour which renders Helmut Newton nudes emerging from a crumbling ruin suggests a sense of perversion that can deciphered through personal encounter and in the work itself.

Having been released from the grip of illness, it is reasonable to ask whether McBurnie will represent his landscape-body of the future as utopian and full of possibility. One can only wonder whether he is ready to take the leap of faith necessary to leave behind him the destruction of his past. Reaching his own threshold, McBurnie, more than anyone, understands the sublime position of standing at the precipice of one’s own limits.

- Dr Laini Burton