QUARTER ACRE

21 October - 7 November 2015

Curated by Adriane Hayward + Verity Hayward

Opening Night | Thursday 22 October 6-8pm

Panel Discussion| Tues 27 Oct, 6pm

On the Home Front: Where is our Great

Australian Dream?

As our city changes and our generation becomes aware that most of us will never own our own home, the divide between reality and the myth of the Great Australian Dream is growing. Panel includes: Cr Meghan Hopper, on Moreland City Council Arts Board and a South Ward Councillor; Karl Fitzgerald, Project Coordinator for Earthsharing Australia and Project Director at Prosper Australia; Jessie Scott, Artist + more. All welcome.

Eva Heiky Olga Abbinga, Adrian Doyle, Jacqui Gordon, Penelope Hunt, Eugenia Raftopoulos + Jessie Scott

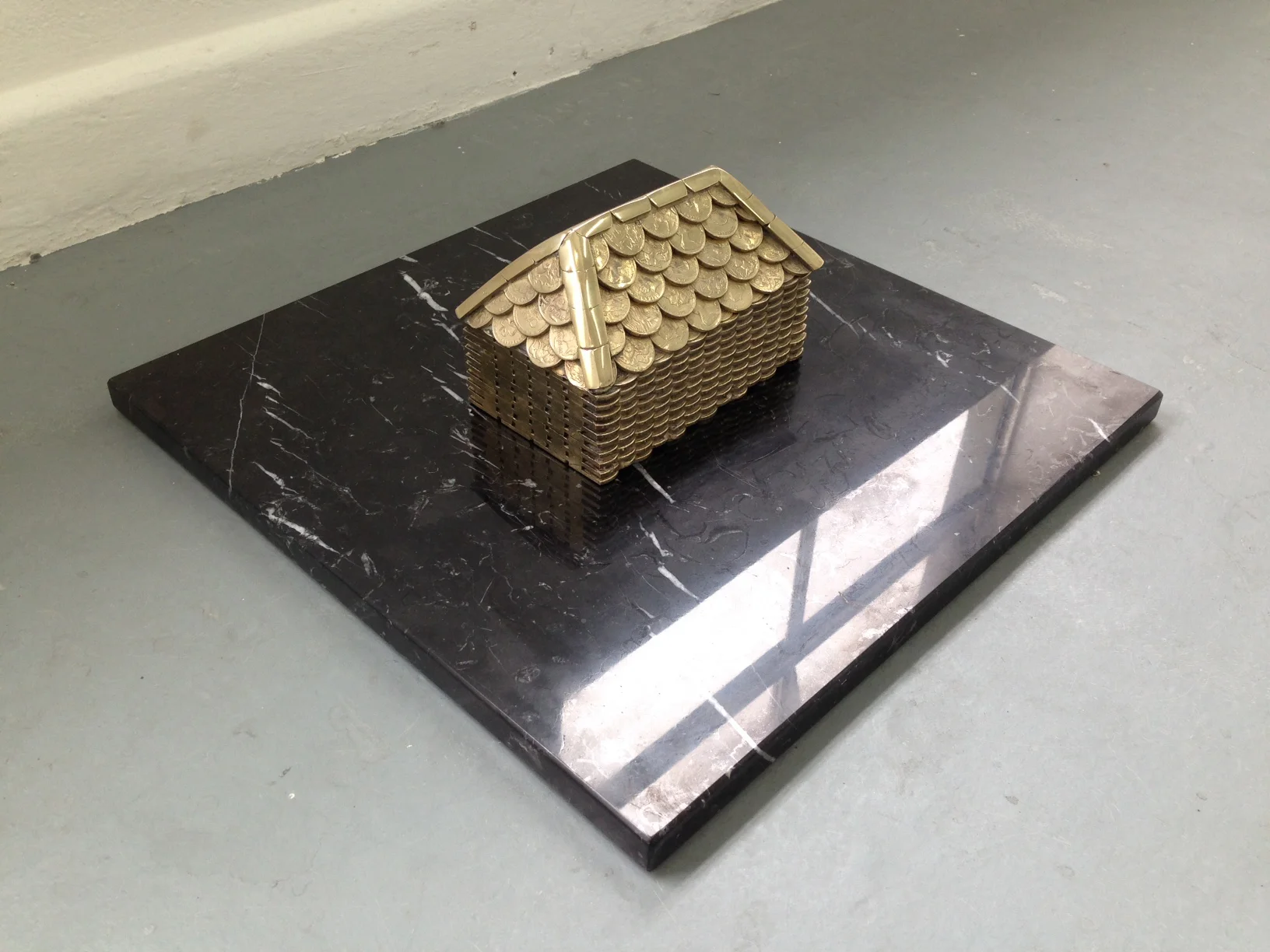

The mythology of the Great Australian Dream tells us that owning a home is a measure of success and stability. However the divide between reality and the myth of the Dream is growing. Deeply entrenched into our cultural sensibility, the Dream is now threatened by the housing affordability crisis, resulting in a cultural dislocation and an uncertain future.

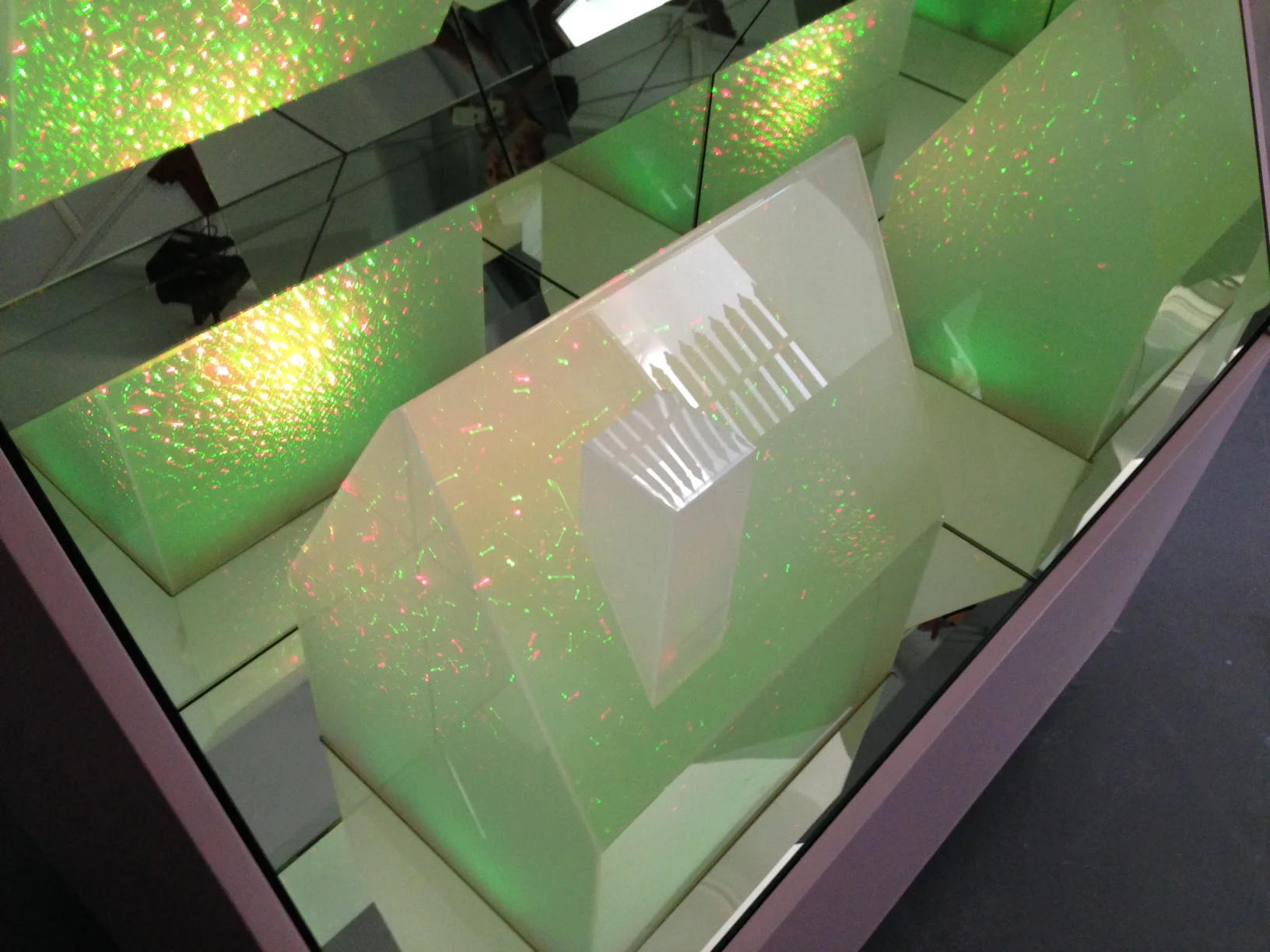

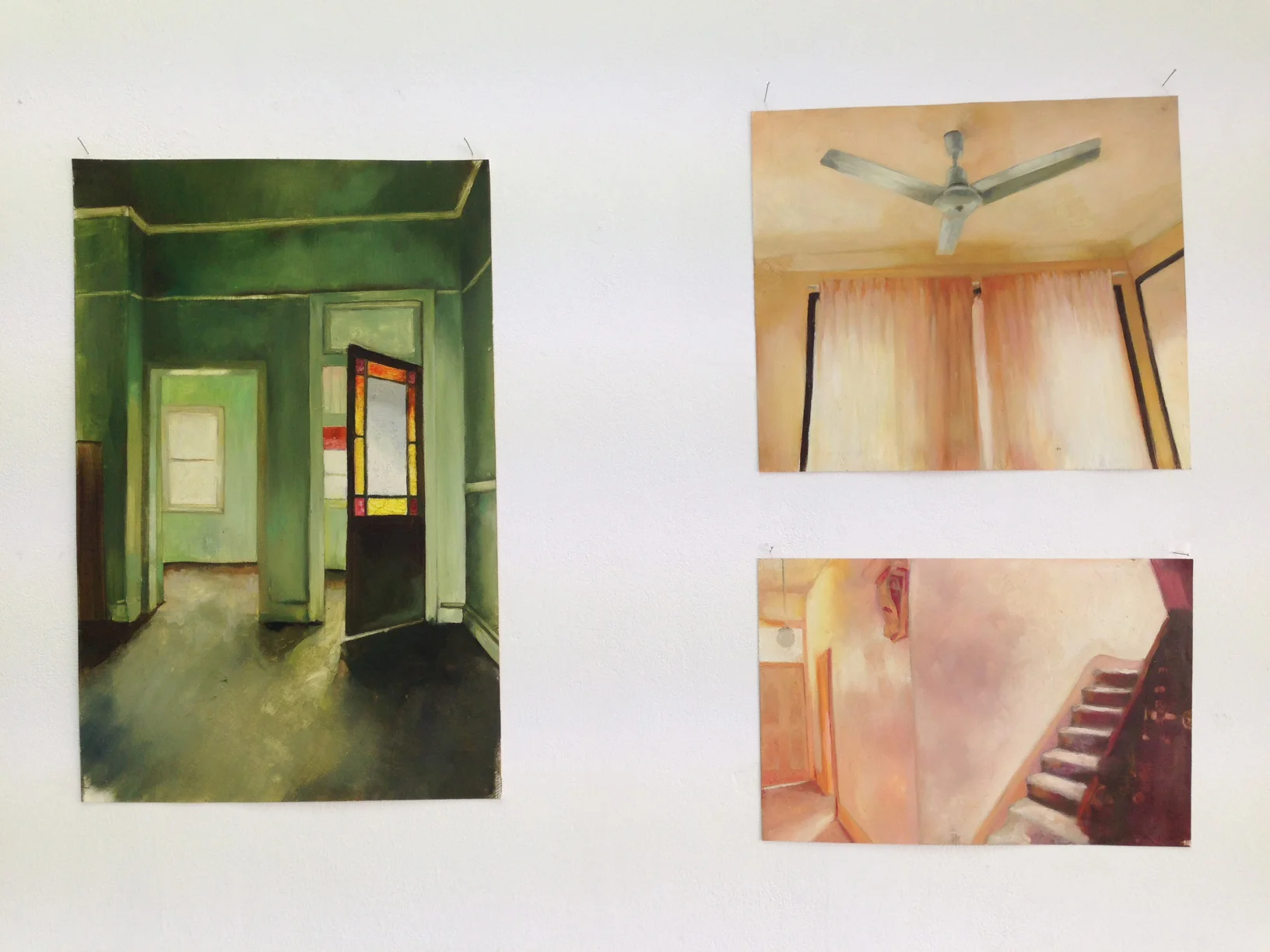

In Quarter Acre, six Australian artists explore the changing nature of the Great Australian Dream. They challenge its present existence and question its uncertain future through imaginings of the home, the suburb, and through their personal histories and memories. The artists reflect on the shifts and changes that have occurred in their cities, and create new concepts for the Great Australian dream within its contemporary state.

IMAGES | Images courtesy of the artist.

SHIFTING GROUND, DISTANT DREAMS

The dream starts like this... We’d own our quarter acre block in the suburbs, or maybe in the inner city. Our street would be lined with houses of modest uniformity – a sense of egalitarian plainness. From one horizon to another, house after house. But we’d have our own little piece of Australia.

The highway is not too far away, a constant hum. We would be stirred from sleep by the rusty chirrupp of a Little Wattlebird. Cars stream down the street – a Sunday rush

to brunch or the beach. Couples walking their dogs propel snippets of conversation through the white-framed windows. Somewhere over the bluestone alleyway someone would fire up a choking Greenfield, and the summery whiff of freshly cut grass would waft over. It would only take about fifteen minutes to groom the small patch of Sir Walter on our quarter acre. In the darkness, audacious possums patrol the top of the blue corrugated-iron fence, side-stepping the tumble of fragrant jasmine that has taken up residence; we would shoo them away from the basil and the thyme with flapping hands. At night the hollow clucking of the pedestrian crossing becomes a metronomic soundtrack, measuring the quiet night. The 24-hour repeat of suburban life, its rhythms become routine.

These suburban bungalows and sun-faded weatherboards, both the staple of the Melbourne streetscapes and the real estate agent’s window are tropes of the Great Australian Dream. The alleyways and laneways are the urban vignettes of the same fantasy.

The mythology of the dream tells us that home ownership can lead to a better life; it is an expression of our success and security and promises a comfortable retirement – the good life. But the reality is the dream has been fractured.

The quarter acre blocks are being subdivided, small brick veneer Californian bungalows replaced by multi-story townhouses pressed together without eaves or verandahs. Square concrete monstrosities puncture the skyline. Where there had been picket fences,where there had been families on porches, kids playing in the sprinkler on a Sunday afternoon, cars sprawled across front yards.

With Australian housing now among the most expensive in the world1, and rising housing prices disproportionate to average wages, the dream has fractured. We are the generation of Australians on the verge of realising they might never own a home. Whether or not this is a cause for concern for us individually, this is something that has never been seen before in this country. At present, one third of Australians don’t own property, the lowest level it’s been since 1954.2 We are the locked out generation.

Price growth exceeds savings, and with that home ownership becomes a distant dream: in Melbourne house prices have jumped 10%, an increase that surpasses the increase to wages. Until the late 1990s, house prices were pretty much in line with incomes, so this wasn’t a problem.3 Property economists have suggested we need an extra $200 per week of savings to keep up with the increase.4 How do we buy a home when the average price of a house is 10-11 times the average wage?

Housing is unaffordable because the market is flooded with investors. High-income earners are buying homes that they don’t really want, but that people want to live in. This means that fewer than half of our homes are owned by the people that live in them.5

State governments are looking at supply in order to mitigate the problem. However, increasing supply for the younger buyers doesn’t actually ensure that high-income investors won’t snap up the extra dwellings. In the city, we build up, in the form of hundreds of apartments – an amended version of the dream. Our city now has a significant excess of apartments, an oversupply. There is infrastructure, community, and no need to commute – all of that for around half a million dollars. But are these dwellings sold to owner-occupiers or will they become yet another investment property, owned by those trying to minimise their tax through negative gearing? Some investors are happy to keep their apartments vacant, the result of which is hundreds of empty dwellings in the city – their original purpose as a home, a place to live seems to be secondary.

And what if we push outwards instead – creating an extensive urban sprawl to keep the dream alive? Perpetuate the dream of the backyard and the block and sacrifice infrastructure, community, commit to a long commute each day? The idea of the continued decentralised urbanisation of cities has its own issues. Being 45 kilometres from the city in order to be able to afford to buy doesn’t appear to be a creative solution to a modern city.

The spatial form of the suburban residential area may not be sustainable and has sometimes been described as an ecological disaster, and those building and developing in this way seem more focused on maximising revenue than building sustainable and harmonious communities.

If some semblance of the land ownership dream is still important to us, solutions have to be considered. The dream, nor its related market, is what is once was. In response some of us will move back in with our parents to save a deposit, some of us will move outwards to those more ‘affordable’ areas, and some will be content with simply not owning. Some will work two jobs whilst getting taxed at the highest rate on the second.

But the notion of the ‘fair go’ that framed the Great Australian dream seems to be absent here...

This exhibition is an attempt to consider solutions, to potentially reimagine our future and the dream that goes with it. Maybe we are stuck in a cultural dreaming; a memory of an idyllic, stress free process that is perpetuated to us through our parents. We might have to relinquish our own quarter acre, our backyard in favour of something shared, something smaller. But maybe it’s an opportunity to develop something better than before – innovate – and consider more sustainable ways of having our own little piece of Australia.

1. Sashka Koloff, Housing affordability crisis, 2015, Transcript from Lateline,

http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/content/2015/s4222696.htm

2. Sam de Brito, Investors lock out a generation from homes, 2014, The Sydney Morning Herald, http://www.smh.com.au/comment/investors-lock-out-a-generation-from-homes- 20140125-31f52.html

3. Sashka Koloff, op. cit.

4. Christina Zhou, What income do first home buyers need to buy in Melbourne?, 2015, Domain, http://www.domain.com.au/news/what-income-do-first-home-buyers-need-to-buy- in-melbourne-20150619-ghq9pf/

5. Waleed Aly, House prices: is the ground beginning to shift at last?, 2015, The Age, http://www.theage.com.au/comment/house-prices-is-the-ground-beginning-to-shift-at-last- 20150610-ghla0f

- VERITY HAYWARD