SOUND SERIES: PERCH

31 July - 2 August 2014

Opening Night | Thursday 31 July 6-8pm

Catherine Clover, Vanessa Tomlinson + Alice Hui-Sheng Chang

Sound Series: Perch investigates the connection between site-specific sound, installation and collaborative performance. Catherine Clover will create an immersive series of works, informed by her ongoing research into bird calls and inspired by BLINDSIDE’s avian perch over Melbourne’s city centre. Ornithological sound will be considered for its raw properties, a series of squawks and chirps, as well as for its function; it will be used as an experimental platform from which to regard concepts of linguistics, behaviour, communication and collaboration. Like a sound art nature documentary, experimental musicians and performers will be invited into Clover’s roost to respond to her works—her installation serving as both an artwork in its own right and interactive score waiting to be activated. The exhibition will thus be as much about the sonic experience as it is about site itself and the building of social and artistic relationships through sound. Collaborators include percussionist Vanessa Tomlinson and experimental vocal artist Alice Hui-Sheng Chang.

IMAGES | Catherine Clover, Alice Hui-Sheng Chang, Warming up in Hong Kong, 2007, photo by Hsieh Jo Lin, Alice Hui-Sheng, Taipei Bus depo, Taiwan, 2008, painting and photo by Chun-Hsien Chien, Catherine Clover, Mid-morning, mild, some clouds, 2014, Urban intervention in Newport, Catherine Clover, Field recording on the Great Wall of China, 2007, Vanessa Tomlinson, Sounding Nudgee, Photo by Sharka Bosakova| Images courtesy of the artist.

PERCH

“Over there... maybe”

Clover gestures at a tiny pinprick of grey on a sheet metal roof. It’s hard to tell if it is a patch-up roofing job gone wrong, a bit of floating city litter that has settled or indeed the subject of our hunt: a pigeon.

Another speck floats over to join the first and together the two begin a rather recognizable bumbling that confirms her initial speculation.

From the 7th story of Melbourne’s Nicholas Building, one has a fantastic view of the city centre—complete with historic buildings, meandering urbanites and literally hundreds of birds. Indeed the view is so good that BLINDSIDE once boarded up the window in silent hopes that its patrons would reflect on the artwork in the gallery with as much esteem as they do the belvedere.

Across the years many projects have referenced this distinctive feature[1], looking outward as a means of inspecting our personal and cultural notions of landscape, of seeing, and of our city. In this exhibition, however, BLINDSIDE is more than just a room with a view; it is a perch from which to consider our avian neighbours, their sky-mapped worlds and complex societies.

As it gets later, our conversation grows increasingly lateral. “I’d heard somewhere that birds use highways and even lighthouses to guide their migrations.”

“Well they certainly use the streets to get around Melbourne. You can see them over there, flying along above the cars." From here I’m lost in thought again, re-imagining Melbourne as an invisible grid of rivers built from wind currents. Cath breaks my reverie by pointing towards the cathedral.

“I’ve some recordings I took from around those benches.”

“Huh?” I crane my necks to see.

“Just down there—along Swanston Street. I might use them... Birds, conversations, tram bells…”

Birds and bells… it’s like in that nature documentary where lyrebirds compose their songs from the sounds of their environment—mimicking everything from other birds to camera shutters, car alarms and even chainsaws[2]. All of these recording processes seem remarkably familiar; apparently scientists from the States have found some interesting similarities between how both songbirds and humans learn to speak[3].

“Say, do you reckon these bird whistles actually work?” There is a deep sonorous inhale followed by a duck-like “Ggguik, ggghh. … Ggghuuiiick!”

As if in answer a few minutes later, a sparrow beak clacks against the windowpane.

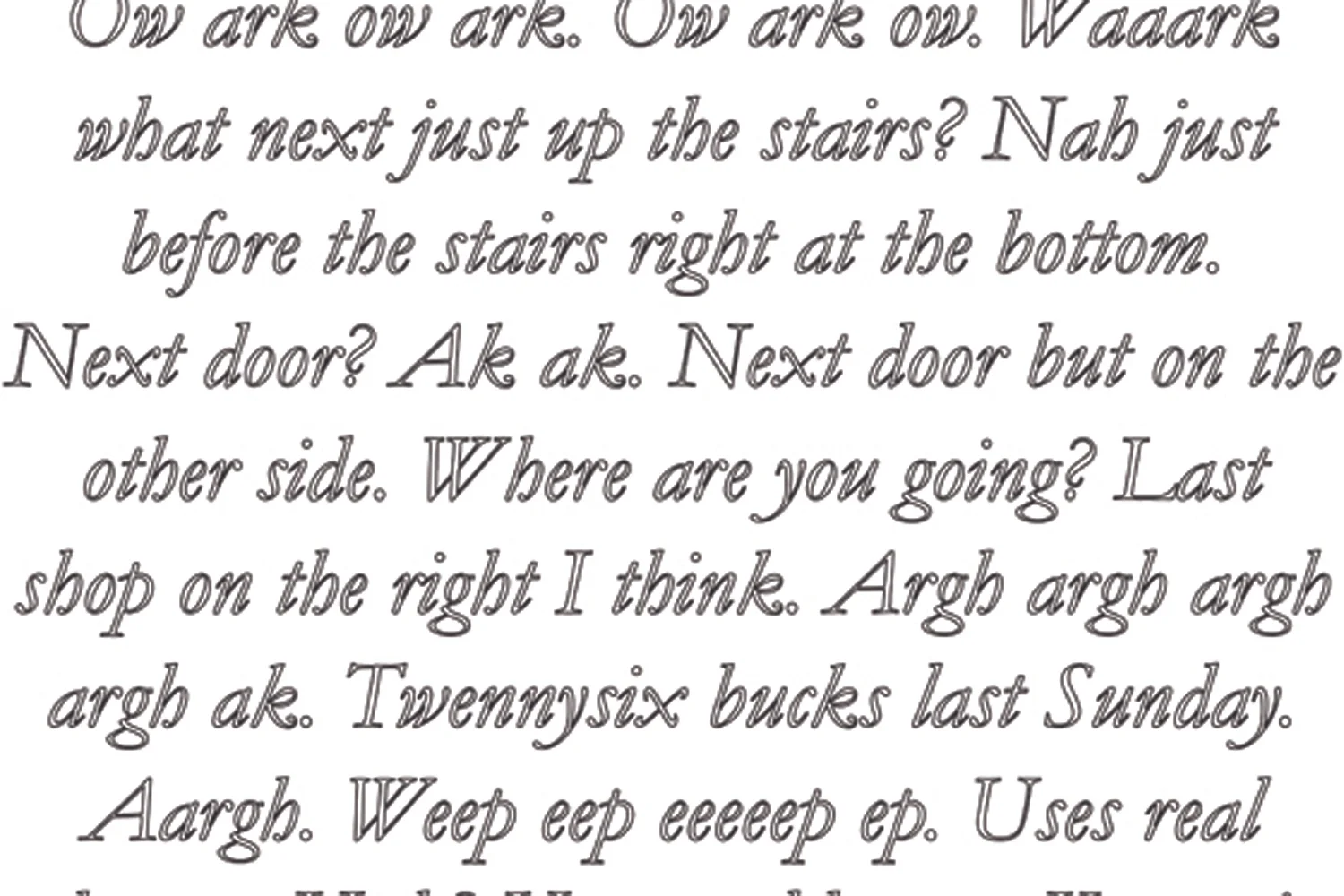

Catherine Clover’s work is an ongoing investigation into birdcalls and behavior. From a skin-deep glance one can see her interests in field recording and soundscapes, of itemizing the sonic environment and translating sounds into onomatopoeic representations. The physical works are a bit slippery; for instance, artworks like the one overleaf exist somewhere in form between authentic sound (as it was expressed), heard phoneme (as it was translated into text), visual representation (as it starkly appears in Garamond), and imagined sound (as it would be re-articulated by a reader). The openness in these works offers us a space for a shift to occur; bird is no longer a flat surface—no longer a four-letter word, a caged pet, the main course for dinner or a noisy inner-city pest. Instead it is an opportunity for curiosity. The further we go with Clover on her exploration into the avian unwelt, the closer we come to understanding something that is far more human and far more primal—as if the tweets, chirps and squawks can be used to decipher something very telling about the nature of language, listening, learning and communication.

“Did you know that they’ve found out that ‘huh’ is something of a universal word? Apparently almost every language on the planet has something like it… and most of them sound the same. [4]”

The thought puts two very different sounds in my head simultaneously: the characteristic lick in Miles Davis’ So What and a sound performance I once heard that featured guttural pre-language vocalisation. The combination is a bit weird, but there’s certainly something to that fine line between instinctive grunt and articulated word.

Clover’s artwork is not only interested in and composed of language; the installation is quite literally a text to be read—or perhaps, to be a bit closer to the mark, a conversation to be had. Clover presents us with works that are ready to be activated: stations of sound, text and object filled with discursive potential. There are words to be sounded out, ornithological stories to be translated and sonic thoughts to be imagined. As such, the exhibition is whole but not complete without an active participant, or in this case two active participants: extended vocalist Alice Hui-Sheng Chang and percussionist Vanessa Tomlinson.

Alice and Vanessa’s practices may be diverse in form, but their chosen instruments are equally direct, immediate and versatile. One can hardly think of anything more primal or base than these two mediums—of taps, thumps, shrieks and groans. Despite this rawness though, both also have an almost limitless capacity and an exquisite delicacy to their tonal range, timbre and sonic texture. Fittingly, these artists will perform a collaborative response to Clover’s “artwork score”, completing it and creating something that is half playful talkback, half conceptual experiment and half collaborative sandbox.

Across the way, over on the roof, the two pigeons we were surveying earlier punctuate the end of our conversation—together they shuffle to the gutter ledge and haplessly fall over it, catching themselves in flight.

Andrew Tetzlaff, 2014

[1] A day, unsung, 2013; Lines of Flight, 2012; Interventions in the Present Moment, 2012; Objects in Space: Insides Outside, 2008; Black Swans, Red Herrings and White Elephants, 2008; etc.

[2] The Life of Birds 1998, Documentary Film, BBC Bristol in association with PBS, UK. directed by Joanna Sarsby

[3] Margoliash D and Schmidt MF 2009, ‘Sleep, off-line processing, and vocal learning’, Brain & Language, vol 115 (2010), pp. 45-58

[4] Dingemanse M 2013, ‘Is “Huh?” a Universal Word? Conversational Infastructure and the Covergent Evolution of Linguistic Items’, PLOS One, 10 Nov 2013