THE ANTIPODEAN

23 March - 9 April 2011

Elizabeth McInnes + Matthew Berka

The Antipodean sees Elizabeth McInnes and Matthew Berka navigate the path of immigration and assimilation within Australian society. Through three video projections, McInnes and Berka examine the ideology and structure of immigration alongside the classic Australian film They’re A Weird Mob. Engaging with both Australian history and pop culture, McInnes and Berka conduct a societal archaeology, exhuming the bodies of the past and placing them, often uncomfortably, within our contemporary context.

The Antipodean is a mixed media installation implicating the Australian film text ‘They’re a Weird Mob’ (1) into the discourse of contemporary capitalism and multicultural identity.

In 1950s Australia, the dependency upon a non-British immigrant workforce was central to economic growth and the prosperity of this country. In this postwar period, a capitalist government sought to advertise Australia as a haven for male foreigners, to encourage the development and further wealth of the country. A variety of tactics where employed to integrate foreigners as quickly as possible. Slogans like ‘populate or perish’ where used with irrevocable authority, however the real success of the assimilation agenda transpired when the media began asserting empathically with the social structures of male dominance, patriotic pride, and Australian customs and idiosyncrasies. The ploy was designed to affirm the linage of the ‘Australian’ more concretely, and bestow upon ‘foreigners’ a method for integration and assimilation into Australian culture.

They’re a Weird Mob is a calumniation of this assimilation strategy. It offers Australia as an antipodean land of masculine utopianism, “(where) A man doesn’t dream in the sun and there are many manly things that must be done in this land that’s shiny and new” (They’re a Weird Mob theme song). They’re a Weird Mob narrates the transition of a foreign man into an Australian paradise, in exchange for his physical labor and the continuation modernist modes of production.

The story from They’re a Weird Mob begins with Nino Culotta, an Italian immigrant who needs parental guidance on foreign Australian waters. His willingness leads him to forget his former occupation as a sports writer, to assume a more socially accepted job as a laborer. Immigrant Nino is treated as an ‘other’ in They’re a Weird Mob, as an object of representation ‘preaching acceptance to appear more fulsome than accurate (2)’ to white Australians.

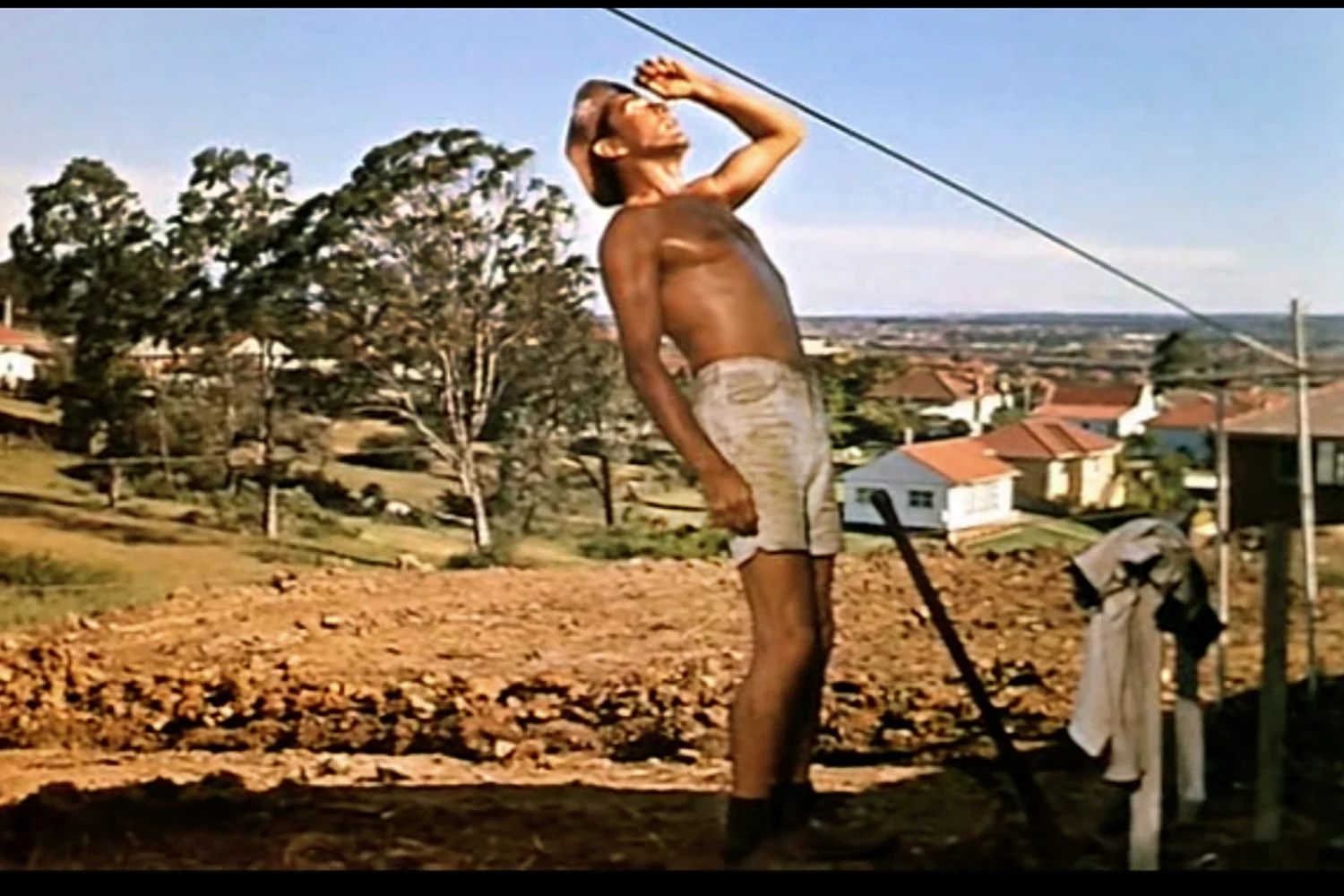

Nino’s transition is presented throughout the narrative as a series of skills and linguistic customs that need to be learnt. The physical preparation of Nino calumniates in a scene 40mins in, where he goes to an undisclosed site to dig the soil with the choice of a mattock or a shovel.

Presented as more of a symbolic ritual than a utilitarian action, the scene is accompanied by music and a strong authoritarian Australian male figure. Through a carefully constructed scene, Nino must to prove himself to this figure, who watches over him, often rejecting his efforts and acting as a presence of tension and pressure. The scene delicately plays upon extensive cultural codes and symbols, without disclosing its ulterior motives.

Our response consists of a multi screen space moving in and out of synchronicity, interacting in negotiation with each other as it shifts between allusion, citation and dissonance.

The first screen presents the original dig scene from They’re a Weird Mob in its entirely on a loop. As a point of reference in the installation, it allows the viewer to observe its deployment of cinematic devices as persuasive mechanisms.

The second screen depicts two ambiguous figures performing the digging action in an isolated dirt space. Centered upon the performance, the scene draws attention to the performer’s engagement and disengagement with the ritual and its problematic ‘utopian outcomes’; promised through a completion of the act.

By reducing the cinematic essence of Weird Mob’s structure, the screen centralizes upon the ideologies embedded within the film and the symbolic mattock ritual. Secluded is the reoccurring close-up of the mattock extracted from the digging scene, re-inserting it into the response as the primary constituent. The shot remains unedited and plays out in real time, depraving the viewer of the gratification that the film offers. The erasure of the protagonist in our response suggests a myriad of potential others; the inverse of Weird Mob’s subjugation of other to a foreign entity which is accustomed to national categorization.

Both screens eschew this outcome through a prolongation of the scene, disrupting of the narrative’s linear continuum. The integration of the other into the culture is not fully realized and succeeds to be attempted in a successive loop. Its implicit motives are contemplated with suspicion; mistrusting the scenes potential as to whether it will come to fruition.

The third and final screen positions the viewer in state of observation, surveying a series of contemporary construction sites in their preliminary stage of development. Shifting between a variety of visual and personal perspectives, drawing relationships between larger mechanical construction and the manual labor ritual enacted on the performative screen. It examines where ideology is potentially constituted and continued, its implications and ties to capitalism. The presence of otherness that Weird Mob attempts regulate is imbued in front, and behind the camera as it scans the space, penetrating its surface as it seeks to negotiate a sense of beauty with the fallibility of our past and present.

As we move into a more globalized world and economy, the currency of Weird Mob’s ideology are both obsolete, yet telling, about the other and ourselves. As an artifact of a bygone era, it demonstrates the effectiveness of media to influence our social values and sense of identity. In an exhaustive attempt to rekindle a relationship with this material, we place ourselves in the position of the other, asserting our own foreignness in a colonized land. This dislocation troubled by a feeling of being inextricably tied to this place we call home.

- Elizabeth McInnes and Matthew Berka

Endnotes

1. They’re a Weird Mob 1966, 35mm film, Williamson/Powell, Australia,

2. Stella Lees, June Senyard, The 1950s, publ 1987.