VERTIGO | ASIALINK

Exhibition dates

Indonesia | 20 March – 15 April 2014 | Galeri Soemardja – Bandung Institute of Technology, Bandung

Taiwan | 9 May – 8 June 2014 | Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Taipei

South Korea | 23 July – 27 August 2014 | POSCO Art Museum, Seoul

Curated by Claire Anna Watson

Boe-lin Bastian, Cate Consandine, Simon Finn, Justine Khamara, Bonnie Lane, Kristin McIver, Kiron Robinson, Tania Smith, Kate Shaw +Alice Wormald

The artists interrogate contemporary life, exploring the fracture, chaos and dislocation that arises in the human condition and in a world which is imbued with flux and change. The experience of dizziness and a loss of perspective are explored within a world that is gripped by an acceleration of time and pace.

Presenting sculptural works, painting, neon, collage, drawing and video, the artists disrupt the ordinariness that can pervade life, building new narratives of human experience. By conveying feelings of anxiety and humour, or by using absurd gestures, the artists in Vertigo attempt to make sense of the world around them, with dizzying effects.

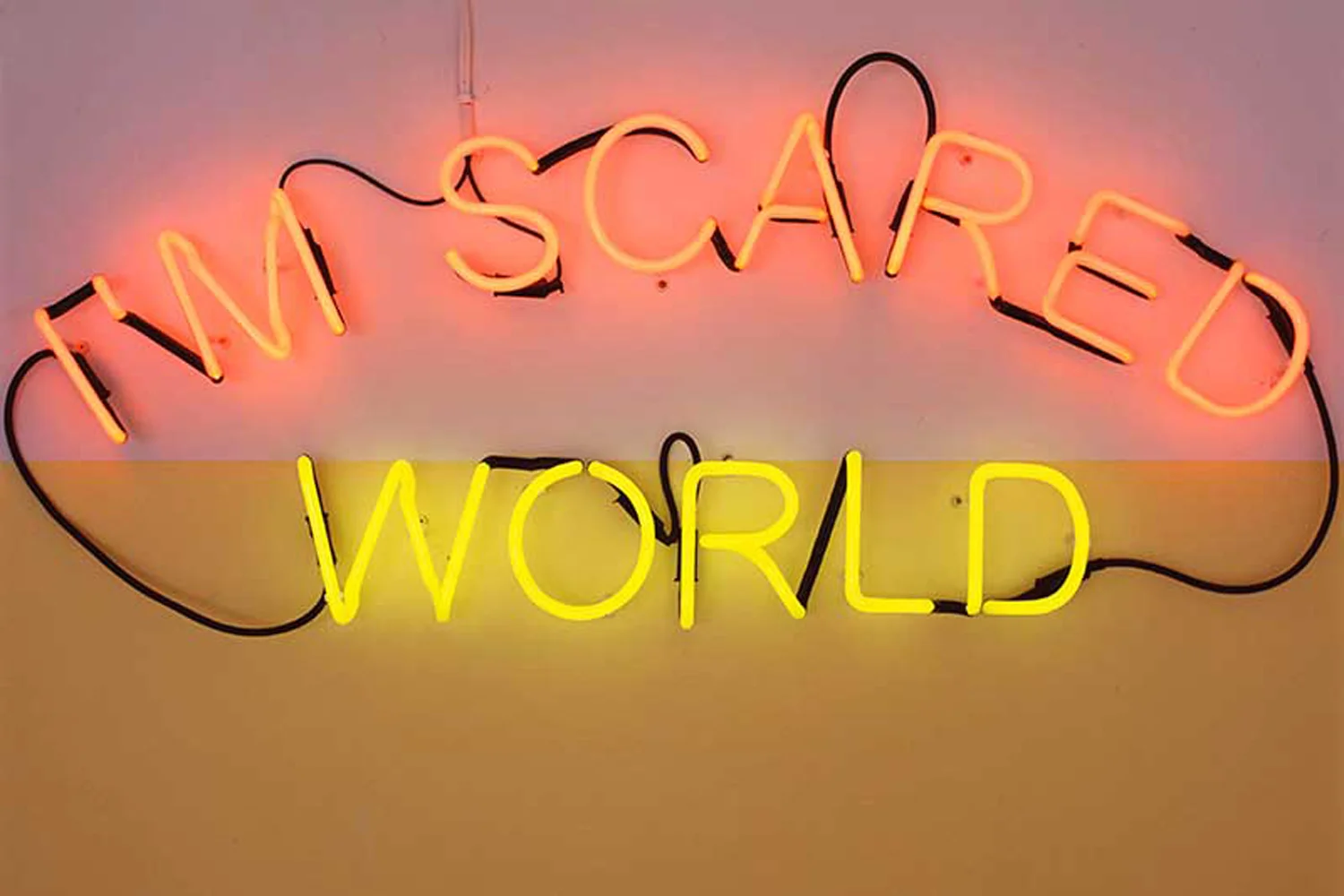

Images | Kiron ROBINSON | I'm Scared World 2006 | neon, 50 x 120 cm | Courtesy of the artist and Sarah Scout, Melbourne; Cate CONSANDINE | Boy #1 2010 | HD Video (detail) | silent | Courtesy of the artist and Sarah Scout Melbourne; Kate SHAW | The Spectator | HD Video (detail) | 4 minutes | Courtesy of the artist and Fehily Contemporary, Melbourne; Bonnie LANE | Like Sands through the Hourglass 2010 | HD video (detail) | 2 minutes | Courtesy of the artist and Anna Pappas Gallery; Simon FINN | Surge Sequence 2012 | HD Video (detail) | 1 minute 25 seconds | Courtesy of the artist and Fehily Contemporary; Kristin MCIVER | Vertigo 2009 | neon, acrylic | Courtesy of the artist, James Makin Gallery, Melbourne and Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney; Boe-lin BASTIAN | Crutches 2013 | Crutches, wooden boxes and acrylic paint | 176 x 47 x 38 cm | Courtesy of the artist;Justine KHAMARA | Orbital Spin Trick (maquette) 2013 | UV print, laser-cut plywood | 50 x 50 cm | Photograph by John Brash | Image courtesy of the artist and ARC ONE Gallery; Alice WORMALD | Giddy Heights 2012 | oil on linen | 122 x 89 cm | Courtesy of the artist and Daine Singer.

Chaos and dislocation in contemporary Australian art

What happens after tomorrow?

Alfred Hitchcock’s character Midge Wood asks the impossible question ‘What happens after tomorrow?’ in the opening scenes of the acclaimed film Vertigo.[1] Impossibility and the uncertainty of what tomorrow may bring seems a suitable place to start when introducing the work of the ten Australian artists featured in this exhibition, which shares the film’s title. There is a sense of the unknown penetrating their practices, and as with the central character of Scottie Ferguson in the movie produced over half a century earlier, the artists explore a world that is not always based on logic, but rather a world submerged in disorientation and fracture. It is this desire to interrogate the unknown that unites the artists in Vertigo.

Boe-lin Bastian, Cate Consandine, Simon Finn, Justine Khamara, Bonnie Lane, Kristin McIver, Kiron Robinson, Kate Shaw, Tania Smith and Alice Wormald embrace vertiginous strategies to perplex and confound their audience. Whether it is through shifts of scale in the natural world, or contemplations on the confusion and paranoia that can affect the human condition, their work traverses a landscape marked by chaos, flux and a slippage between dreamscapes and reality.

Presenting sculptural works, neon, painting, collage, drawing and video, the artists disrupt the ordinariness that can pervade life, building new narratives of human experience. By conveying feelings of anxiety and humour, or by using absurd gestures, the artists in Vertigo attempt to make sense of the world around them, with dizzying results. The multifarious artworks presented are all attributed with an artistic process, a conceptual framework or subject matter that speaks to the sensation of vertigo. Gripped by a state of perpetual anxiety in a world that is becoming more and more frenetic, the artists explore the breakdown between what is public and what is private, and what is real and what is imagined.

Poised at the precipice of joy and despair, of flight and trauma, are Cate Consandine’s confounding video works, Boy #1 and Lash. Taking as their departure point the human subject, Consandine not only mines the complexity and ambiguity of being human but also investigates our relationship with time itself. Seeming to experience the full force of gravity is a young boy in Boy #1. Enmeshed in the frontier of a psychological landscape, it is as much an evocation of the child’s burgeoning adolescence as it is an insight into the deeper nature and debilitating effects of anxiety. He squirms and spasms, his eyes searching wildly. It is almost as though he has spun around repeatedly and then fallen to the ground. The viewer is left questioning: is this ecstasy or catharsis? Trance or hypnosis? Is it possession? Consandine carefully eschews any grand narrative in favour of the continually looped and undecipherable moment. This is also the case in Lash where the primitive fetish of the mask suggests a magic rite charged with the powers of deception, vertigo and simulation. The lurid feathers affixed to the male subject’s eyes flutter in perpetuity. Through this simple embellishment, the human form becomes animated into a hyperreal encounter with the animal kingdom, but we are not satiated with the luxury of context; Consandine’s sensibility is one of poetic inference and haunting beauty.

In the mischievous provocation Jellies from her Coupling series, Boe-lin Bastian places two jellies on top of an old washing machine. They jiggle in a wonky performance that is dictated by the washing machine’s inner workings. The absurdity of the piece is shared with other works by Bastian. In her practice, everyday objects are defamiliarised through a deconstructive process which infuses them with life and humour. Plastic bags are the chosen medium in Big/Little from the same series. They spin idly in a kind of game that is strangely compelling; it has the hallmarks of senselessness and yet the result is surprisingly poetic. As the bags filled with water collide and contract in a playful dance, at times spinning uncontrollably, they draw you in. You realise, of course, that humans are animating their movements, and that at their source the bags are vehicles for acting out the somewhat ludicrous power struggles of their operators. Bastian tinkers with stratagems of equilibrium. In doing so, she reveals the precariousness which haunts our sense of stability. She interrogates and critiques our propensity to consider our world and our psychological fortitude as resolute, unshakeable. In Crutches, Bastian assembles orthopaedic crutches atop a series of wooden boxes to create a structural piece that resembles the mechanisations of the body. An awkward fragility penetrates the sculpture; it is but a ghost of the human form. Whilst motionless, it seems to evoke the ability to get up and walk out of the room. Crutches is a relic of stability caught in a moment of discontinuity, defiant against the laws of gravity.

Simon Finn’s drawings and new media works reflect the artist’s abiding respect for and mastering of computer-generated imagery, in particular polygonal modelling.[2] In his renderings, Synthetic Surge and Downward Spiral #2, Finn devises a creative process for capturing motion within the restricted medium of charcoal. Both works are conceived through a computer-aided process based in mathematical precision and simulation. Synthetic Surge, like its video-based counterpart of the same title, depicts the devastating effects of an imagined tsunami inspired by a plethora of imagery obtained from the Internet. This slippage between what is truth and what is fiction is a line Finn traverses with great austerity. Downward Spiral #2 extricates the NASA Mars Rover camera from its widely associated context of the alien landscape of Mars, staging it within an entropic spiral that whirls it into non-existence. With his fondness for deep-sea diving, the human inclination to explore new frontiers is one Finn appreciates all too well. The camera’s dizzying demise into the underworld speaks of the broader misgivings of our society—perhaps the perceived pointlessness of pursuing exploratory missions when our planet is already gripped with social and economic imbalance, combined with the knowledge that the natural and man-made disasters that afflict our world may threaten the human species itself. Finn’s dystopian imagery suggests that as our world continues to whiz past at faster rates, a state of vertigo is irreversible. His video work Alarm enunciates these anxieties. Based on a tsunami warning tower the artist saw whilst on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, the alarm signals an impending and unnameable calamity.

Where Finn’s practice is based in mathematical and scientific analysis and data, Justine Khamara’s work is deeply embedded within the psychological. Her painstakingly crafted works reflect the hysteria of occupying multiple psychological states. They also embody the somewhat schizophrenic condition of the digital age and hyper-consumption, where no one is free from constant surveillance and the ever-present repetition of visual imagery. In Khamara’s practice, the multiple and oftentimes ‘virtual’ guises we create for public and social environments are revealed as moments of construction, interconnected but distinct. Her work is also a deeply personal interrogation of social and familial relations, which expands the tradition of portraiture into illuminating territories. Consider the photomontage sculpture Now I am a Radiant People #3, whereby the artist has created a series of spheres colonised by hundreds of cut-out photographs of a man’s face at various angles. As the rippling fractal-like imagery ascends to the vertex, the man’s disembodied face looks further and further downwards. With its reptilian skin, the top constitutes a shield of scaly protection, whereas in the centre, the man faces outward, his gaze interlocking with ours, exposed and vulnerable. Similarly circular and beautifully conceptualised is Orbital Spin Trick #3, which in its sense of movement and architecture seems to orchestrate the mechanics of planetary rotation. A face is here laser-cut into multiple components that when divided offer a kind of after image. The contour lines coalesce and interlock. The spatial experience of this sculptural work is paramount; the viewer is intricately implicated in the work as each angle reveals something new. Rotational Affinity and Rotation Around a Fixed Axis #2 and #3 speak to the forces that divide and connect us. Through repetition and with psychological intensity, Khamara ruptures social and cultural identities.

Bonnie Lane’s video works manipulate everyday phenomena into something otherworldly. In her majestic work, the kaleidoscopic Make Believe, Lane meditates on the fractured representations of childhood. Devoid of personal and physical attributes, the young female dancer that Lane depicts is stripped into an abstraction of humanity. The alluring nature of innocence is the subject. When witnessed in its full installation, with its perpetual motion, time itself seems to stop still. The axis of meaning in Lane’s works oscillates between the minutia of the everyday and the wondrously uncanny. In her critique on futility, Life is Pain, the harmless actions of a goldfish catapult the viewer into a reverie firmly rooted in what is sometimes experienced as the banality of life. Lane’s ‘unspectacular’ goldfish is ‘constantly struggling to stay the right way up, but always being defeated’.[3] Its disorientating trajectory charts a course that inevitably returns to its tragic state of captivity, as is the case with the doomed mouse in her video Like Sands Through the Hourglass. The mouse-wheel that services the fitness needs of this mischievous creature embodies the aimlessness of incarceration and the trivialities of the everyday. The rotational mechanism of a washing machine meanwhile, as viewed in An Ordinary Grind, can whirl your psychological state from the prosaic into soulful introspection. Lane’s works, often haunting and dreamlike in their imagery, reveal a yearning for an alternate world.

A dreamlike quality also pervades Kate Shaw’s paintings; they emit an aura of blissful alchemy. The fluidity of the paint is modelled into landscape formations evoking the fantastical and sublime. Yet, in slipping into the medium of video, her work takes an almost sinister turn. The benign paint flows like lava down a volcano in The Spectator—her inaugural and phantasmagorical video. In this work, we witness countless spectacles of the world being witnessed by others—the turbulence and wonders of the globe conjoin in a cacophony of colourful interventions. The marvels of the natural world, whether it is experienced through mind-blowingly large aquariums, natural disasters or the environment, are all consummated through the role of perceiving. The artist states, ‘I am seeking to draw out the ambiguities of how technology has distanced our relationship to the natural world whilst creating more immediate access to spectacular and disastrous natural events.’[4]

It is not just our relationship with nature that has altered through contemporary technologies; our identities and transgressions have migrated, propagated and even distorted into the vortex of social media, shifting our identities and sense of self. With the rise of social media, our rights to privacy are jeopardised, and we succumb to collective inertia as capitalism and social media entrepreneurs garner every aspect of our personal lives.

The propositions within Kristin McIver’s works Thought Piece (What’s Going On?) and Vertigo expose the glitzy seductive powers of capitalist culture, broadcasting the systems that manipulate our worldview. Thought Piece (What’s Going On?) forms part of a much larger installation involving five other ‘thought pieces’. With steadfast resolve, they project the private insecurities, as well as thoughts and public comments made by the artist in social media. Enacted by the viewer, courtesy of their motion sensors, they flick on to reveal questions from online forums, prompting those that are ‘connected’ to share their lives. The eerie truths of our increasingly digitized ‘socially-connected’ world are examined by social media commentator Andrew Keen who states, ‘…the incessant calls to digitally connect, the cultural obsession with transparency and openness, the never-ending demand to share everything about ourselves with everyone else—is, in fact, both a significant cause and effect of the increasingly vertiginous nature of twenty-first-century life.’[5] McIver critiques this obsession suggesting that the ubiquity of the Internet creates an overwhelming sense of delirium in our social relations. The pile of bricks with disconnected words and disassociated phrases entice us to extract and decipher meaning. The mound embodies the fractured psychological state that can persist when bombarded with messages within this global culture. The instability of the world, and the deficits of semiotics are also highlighted in McIver’s Vertigo. The words ‘This Way Up’ are stuck in an internal dynamic never able to quite reach the viewer with its intended meaning. The dissolution of words as they fragment and distort, recalls the illusory capacity and distorted nature of the social media age.

Mass communication is also the field of inquiry for Kiron Robinson. The visual world can provoke and aggravate the experience of vertigo. It is difficult to escape the dark humour penetrating Robinson’s work I’m Scared World where the vulnerability of being human, and perhaps the most profound fear, is not only resolutely declared but in its starkly lit neon, it is glorified. To propagandise such inner turmoil is simultaneously horrific and hilarious. As we navigate the inherent trauma of this work, we come to sense that while there is a sense of urgency, there is also a need to laugh at the world. Robinson offers a reprisal to this torment in My Head is my Home, my Head is my Home. His answer to the hyper culture of our globalised world is psychological resilience, heightened by the minimalist environment of the object’s white void. Here, you may sequester; you can escape the global network into a private space with only your subconscious to fashion a world of inner secrets, delusional, accepting or meditative states and the projection of anxieties, hopes or fears.

It is not just modern technologies that have brought vertigo-inducing qualities to our lives. The boundaries of distinction have blurred in modern science too. Biotechnologies and genetic engineering have enabled cross-pollination and hybridized life forms. This expanding field is an interesting backdrop to consider in terms of artist Alice Wormald; her paintings assert an air of sublime confusion. What is this strange foliage of the underworld? She manipulates her subject matter so that what we thought we knew is somehow distorted. Microcosm and macrocosm are intermingled to become one; they emit a hauntingly austere beauty. The cut edges of paper that she mimics with paint hints to the collage that conceived the finished work. Her source imagery for Untitled #5, Untitled #6 and Giddy Heights was derived from photographs in nature journals. Her paintings transform these archives into an intense composition that oscillates between creamy fluid forms and lurid and iridescent patterning. Within her work we see real and imagined geological formations and flora. The strangeness engendered through this process is one of subtle disorientation.

Afflicted by anxiety and a seriousness that pervades contemporary life, some artists propose other agencies for change. Humour is the aesthetic and performative device explored by Tania Smith. The interventions captured in her Untitled series cry of disequilibrium, with hilarious results. Smith’s propositions are absurdist gestures that seem to blithely punctuate the landscape with colour and movement. Invoking the spirit of the whirling dervish, a state of exaltation presides, although they reveal an unsettling undertone. The activities that her protagonist engages in, whilst innocuous, speak of a need to separate oneself from the status quo. The motivation for such a need is not articulated, but the audience can only assume it is due to what many perceive as the drudgery of everyday existence. That these desires to engage in ridiculous acts must be kept secret (as evidenced by the woman stepping out of her reverie with blatant nervousness), speaks to a society which restricts behaviours and pursues coveted norms in its governance. Smith’s character is not alone in her yearning for freedom—we all harbour a desire to break free, albeit occasionally.

So, what happens after tomorrow? Lacking prescience, this is of course an unanswerable question that strikes at the heart of this exhibition. The bold offerings of the artists in Vertigo articulate the psychological repercussions and sense of dislocation that arises when considering the uncertainty of our world and its future. With environmental catastrophes, inequity and global conflicts on the rise, and new technologies—which enable new modes of surveillance, monitoring our socio-cultural landscape, life today is shrouded in uncertainty. Do these works embody gravitas and signify a demise of hope? Some teeter on the edge of despair, yet cutting through their solemnity is a sense of exuberance for the multivalency of life and an awareness that there is no fixed notion of the world. They invite us to contemplate the volatility of humanity.

If we think that attempts to overcome our dizzying contemporary world are in vain, we only need recall the optimism of Hitchcock’s central character Scottie when he tells Midge that (after tomorrow) he can overcome his fears a little bit at a time. ‘It’s a cinch’, he declares.[6]

Claire Anna Watson